Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, commonly referred to as MERS, seems to be lessening its grip on South Korea after infecting roughly 150 people and killing 16 since mid-May. The outbreak is the largest number of cases known outside of the Arabian peninsula, where, since 2012, 1,100 cases of the virus have been confirmed, with roughly 40 percent ending in death.

South Koreans welcomed the news of a slowdown in the outbreak that prompted President Park Geun-hye to enact sweeping quarantines and school closings after an initially slow response led to a spike in confirmed cases. The quarantines, along with cancellations by tens of thousands of tourists has left citizens anxious about going shopping and to ball games and other public events that could put them at potential risk. Empty stadiums and the 17 percent drop in retail sales reported the first week of June reflect a near paralysis in the country’s daily doings and have struck a political blow to the tune of 7 percentage points in Park’s former 40 percent approval rating. While the news is likely to mitigate tension among the public, the economy is expected to continue to slow because of MERS and has led the country’s central bank to slash its key interest rate to historic lows.

This intense pressure has serious psychological implications. South Koreans are a crisis weathered people due in large part to the ongoing situation with their notorious neighbor to the north. But in spite of their usual ability to roll with calamity and take it more or less in stride, MERS and its associated economic, social and political implications has swiftly exacted a harsh toll on their collective psyche and in the space of one month, appears to have left them uncharacteristically shaken.

The South Korean outbreak has also lent a new urgency to the global information gathering process and helped to fuel research responsible for the recent discovery of two mutations that allow the virus to make the leap from animals to humans. Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are more closely monitoring the virus to understand its source origin, how it spreads and various risks it poses to the public. While progress is forthcoming, there is much to be learned.

Symptoms and Epidemiology

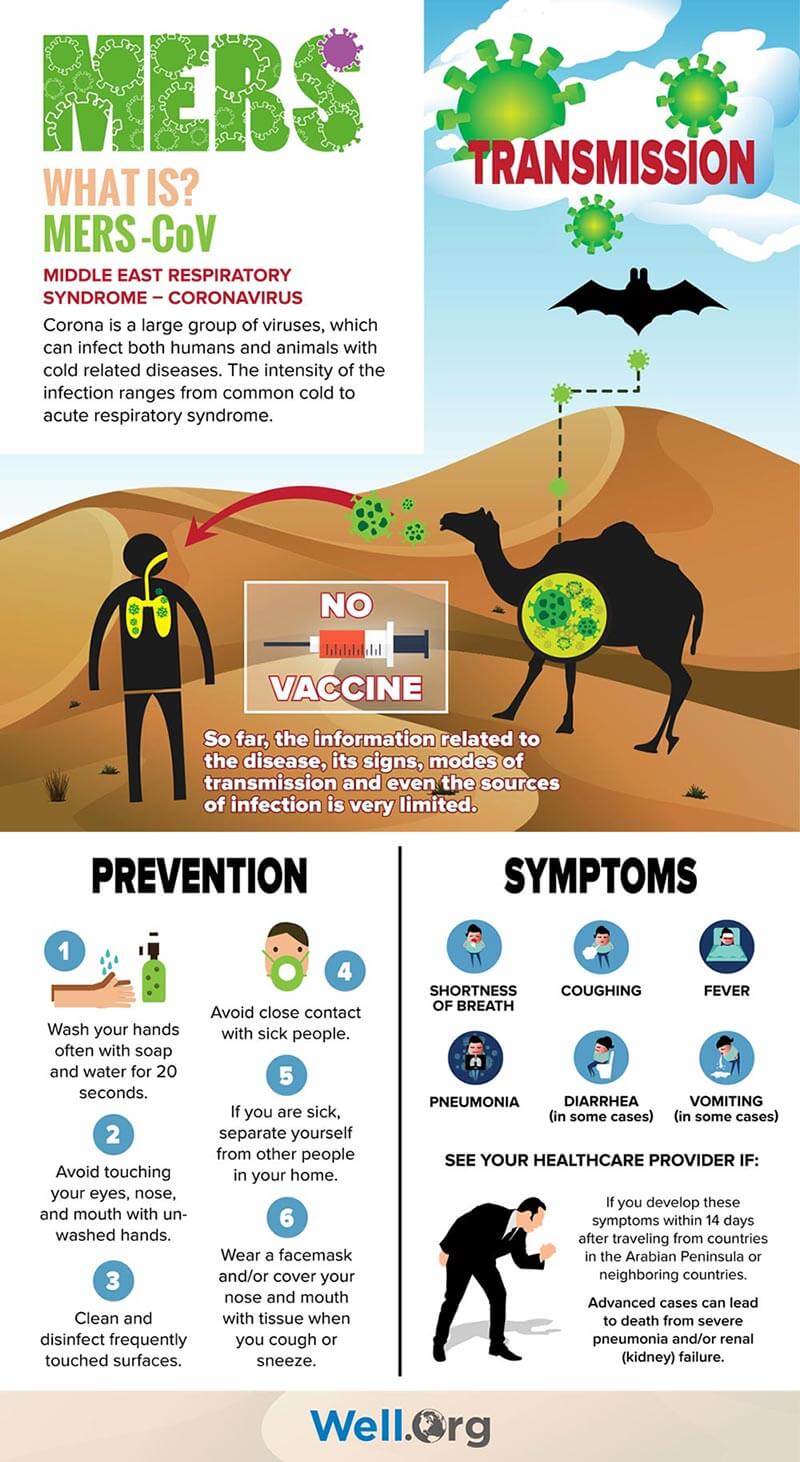

MERS Coronavirus (MERS – CoV) causes severe acute respiratory symptoms including fever, cough, shortness of breath, vomiting and diarrhea and is often compounded by more serious complications such as pneumonia and kidney failure. The mortality rate hovers around four of every 10 patients diagnosed, with most deaths occurring in people with an underlying medical condition. Those with conditions such as diabetes, cancer and chronic lung heart and kidney diseases as well as those with weakened immunity in general are thought to be more at risk for contracting the disease as well as for developing a severe case that may lead to death. The virus has an incubation period (the time between contact with the virus and the appearance of symptoms) of about five to six days, but can range as much as two to 14 days.

Like other coronaviruses, MERS-CoV is thought to be spread through contact with the respiratory secretions of an infected person’s cough, however, this has not been definitively confirmed as the only method by which it spreads. So far, it is known that the novel coronavirus responsible for MERS is the same as that which caused the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak in 2002 and probably originated in bats. Experts suspect camels as the intermediate host (the animal linking the infected bats to humans) but have yet to discover conclusive evidence. By contrast, scientists took a mere four months from the first confirmed case of SARS to determine that the virus was transmitted to humans after spreading from bats to civet cats raised for human consumption.

The time disparity between the speed of information gathered for SARS versus that of MERS is thought to be linked to a few critical factors. The mortality rate of MERS cases is four times that of SARS, but is considered less of a global threat due to its relatively slow outbreak speed and its tendency to disproportionately affect older individuals and those with pre-existing medical conditions. In contrast, SARS spread rapidly, infecting 8,000 primarily young, healthy people within an eight-month period. What’s more, SARS was a widespread global outbreak with cases divided equally among men and women, whereas so far, MERS disproportionately affects men at a rate of 65 percent, suggesting a possible occupational or cultural component to transmission, and until the current situation began last month in South Korea, was previously limited to the Arabian peninsula.

Here at Home

After often sensationalized news coverage surrounding the recent Ebola surge in Africa reached peak saturation levels and led to widespread public fear and even panic in America, it is important to emphasize a calm and measured attitude with regard to MERS.

Experts believe the risk of contracting MERS in the United States is very low. So far, there have been only two reported cases of MERS in the United States. Both were diagnosed in May of 2014 and though unrelated, both cases involved health care providers who had contracted the virus in Saudi Arabia where they lived and worked before traveling to the US. One case was diagnosed and treated in Indiana and one in Florida. After being hospitalized, both fully recovered and were subsequently discharged.

Prevention and Treatment

There is currently no vaccine for MERS-CoV. While the US National Institutes of Health is exploring the possibility of developing a vaccine, much information is still needed about the virus. There is no specific antiviral treatment protocol for the illness, but individuals are encouraged to seek medical intervention to help manage symptoms. In severe cases, patients will receive medical care to support vital organ functions.

With regard to prevention, the CDC recommends these everyday measures and a common sense approach to MERS similar to measures taken to prevent other more common viral respiratory infections. Once again, cool, calm and common sense rule the day:

- Frequent hand washing with soap and water for 20 seconds or use of hand sanitizer when soap is not available

- Covering a cough or sneeze with tissue and proper disposal of tissue after each use

- Avoiding contact between unwashed hands and eyes, nose and mouth

- Avoiding personal contact such as kissing, or sharing cups and utensils with sick individuals

- Cleaning and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces and objects such as counters and doorknobs